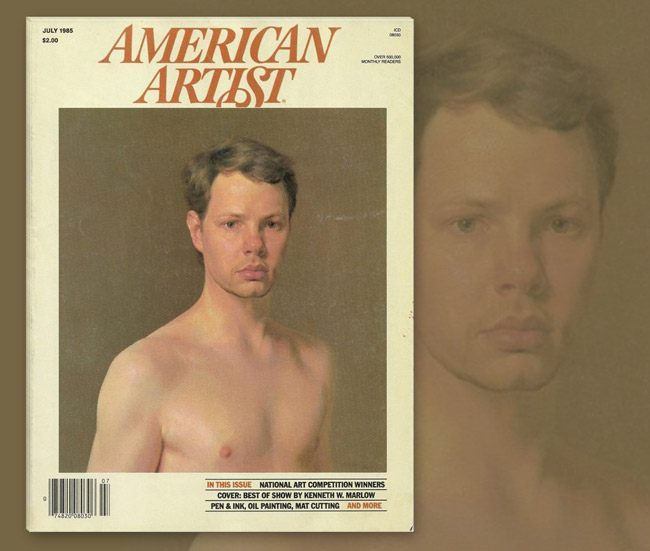

The Barnstone Studios were mentioned in Robin Longman’s editorial essay, “A Serious Look at Art Education”, in the July, 1985 issue of The American Artist magazine.

It is gratifying to have one’s views considered along with those of nationally important educators who are associated with undertakings such as The Getty Center for Education in the Arts and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is also gratifying to observe a new mood among those who concern themselves with the teaching of art in the American public school system. The Fine Arts have been rediscovered along with a relationship that has now been seen to exist between art and its sister disciplines: music, philosophy, aesthetics, and language. It is difficult, however, to note this new excitement without lamenting how completely these relationships have been ignored over the last thirty years of art education.

The pendulum has swung with a vengeance. To redress the failure of the whole system, a new generation of movers and shakers is about to bury us beneath a landslide of verbiage. Words, not deeds, are the stock and trade of the administrators of public education. We are in for a whole new set of words, but there will be little change unless the training of art teachers and the existing philosophy of artteaching is utterly revised.

The last generation of new ideas will have to give way to something more substantial than another generation of newer ideas. Art teachers are going to have to learn to draw. To do this, they will have to be taught the fundamental language of visual literacy: design.

It is not difficult to understand why no one has been willing to address the real problem. It takes some seven years or more to learn to draw reasonably well. That is the real problem.

One has to be very patient to address that problem seriously, and one must be willing and able to sustain a lengthy commitment which is capable of surviving trendy changes in the art world.

Genuine studio instruction will have to replace the present diet of “experiences” and “exposure” so prevalent at art teacher-training colleges. That which is the art student’s heritage will have to become the real substance of art education. Demands for creativity will have to give way to the broadcasting of genuine information. Art teachers will have to be taught the proper use of the language of marks and touches which they must fully understand before they can, in turn, hope to teach its use to children.

And a very simple truth will have to be accepted: the training of an art teacher must begin in kindergarten. Until that is understood, no sumptuous reports, no one-shot, remedial, hands-on in-service programs, no teacher-retraining sessions or other forms of emergency treatment are likely to alter the endless production of cut-and-paste refrigerator art which our schools have invented.

The pendulum has fully swung and its arc has focused our attention on the need for a unifying philosophy among art administrators if there is to be any change for the better in art teacher-training and any subsequent improvement in public school instruction.

A child will have to know that a sequence of levels of training await him and that orderly instruction will provide understanding, authority, and skill in the use of design languages. Sequence and order are essential to the mastery of art as they are to any other subject.

When we laud the spontaneity of a student’s work as a measure of teacher effectiveness, we make a serious mistake, for the role of the teacher is to assure the young student mastery of his tools so that they may be used creatively. When spontaneity replaces mastery we may find artlessness, but we never find art. Pity the “trained” eye that cannot discern the difference.

Can you imagine a school that so values baby-talk that it deprives its students of the skills necessary to speak our common language effectively?

An honest learning situation is one in which real information is offered progressively by trained teachers working in concert to promote standards of excellence. Children who are given the tools to express their ideas and feelings will express them more freely and articulately when they enjoy the confidence provided by understanding.

If we wish to restore respect to the subject of art and to the profession of art teaching, our subject will have to be taught with the same seriousness one has come to expect in other subjects.

We must also accept that we cannot teach art. Artists create art. We cannot produce artists. Inspired individuals make of themselves artists. However, if we broadcast valuable information about our subject, we will accomplish something of worth.

Only through responsible teaching practices can we achieve something like visual literacy in this country, and only through the teaching of classical drawing can we effect a change for the better in the teaching of art in the American public school system.

Jacques Barzun has written: “—does Art include acting, scene-painting, directing, film-making, journalism, broadcasting, photography, weaving, pottery, jewelery-making, batik, macrame—the list can be long if Art includes all the crafts. . . But the serious question to ask yourself is, ‘Which of all the namable arts and crafts are in fact teachable in school?’ None completely, that is sure. The school cannot turn out a painter, a weaver, or a film-maker, no matter how much talent. These two facts lead one to wonder whether any fundamentals can be found that underlie several forms of art.’ Is there something which is to the arts what mathematics is to the higher mathematics, what reading and writing are to literature and all other written discourse? Clearly, the rudiments of music serve in just that way the dancer, singer, and instrumentalist, as well as the composer, critic, and amateur of music. Likewise drawing serves all the arts and crafts that consist of making visual patterns. The photographer and film-maker work with design as much as the sculptor, scene-painter, weaver, jeweler, or dress-maker. What is more, the rudiments are equally useful in the sophisticated and in the popular form of every art.”

Let’s hope that, after generations of neglect, we can find sufficient qualified drawing teachers to restore art to its rightful place in our schools.

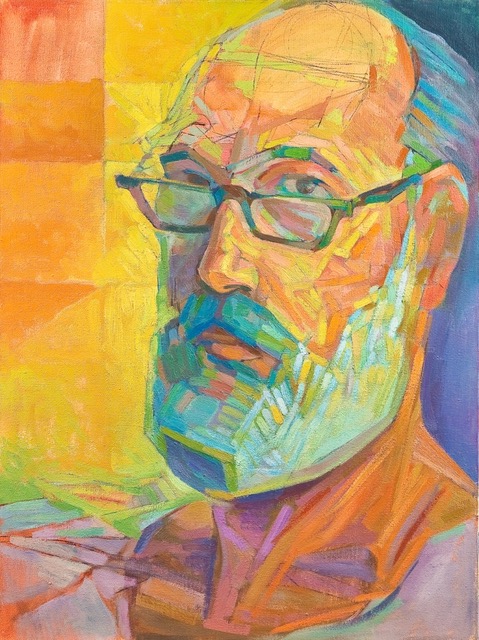

Classical Drawing by Morandi

Let Us Pretend

Somewhere in the universe there is a planet upon which a very exclusive community boasts of an artist’s club to which only those masters who have contributed mightily to their great traditions have been offered membership. This is truly a gathering of artist’s artists.

I have discovered a way to visit this uncommon club. Please accompany me. If you are very quiet, you will be able to see without being seen and to hear without being heard. However, I must warn you, not all of the artists whom you would have expected to find here have been invited.

The conversations are animated by talk of craft, technique, markets, and the prices others are earning from the sale of one’s work. Tonight it is Morandi who is lamenting the passing of the great princes of commerce and the Church: the worthy patrons. He observes with gratitude that he still has a small circle of followers despite the fact that the world seems to be dominated by television, Sunday painters, block-buster exhibitions, which seem only to please the accountants who direct the major museums, and coffee-table books on art which disfigure one’s color and are filled with gossip instead of useful information. It seems no one is willing to discuss provincial museums or what passes for art instruction

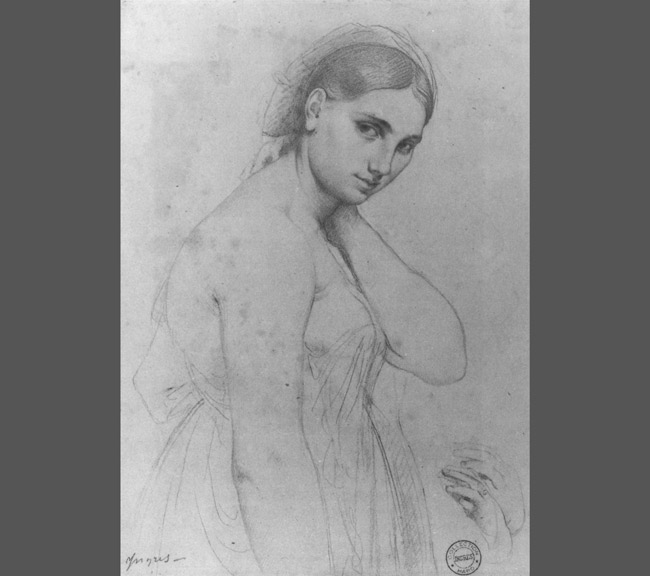

Classical Drawing by Ingres.

Ingres chides Picasso for the haste and lack of integrity he often showed in allowing sketches and puns to be sold at astronomical prices. The Frenchman adds that he hardly thinks making fools of collectors, art historians, and art critics amusing: not by broadcasting shoddy work. Pablo, in turn, implies that Ingres is something of an old maid. Nobody laughs.

Michelangelo notes that at the end of his life he had his assistants destroy any of his work which revealed a struggle or was not up to a standard which he was prepared to sign.

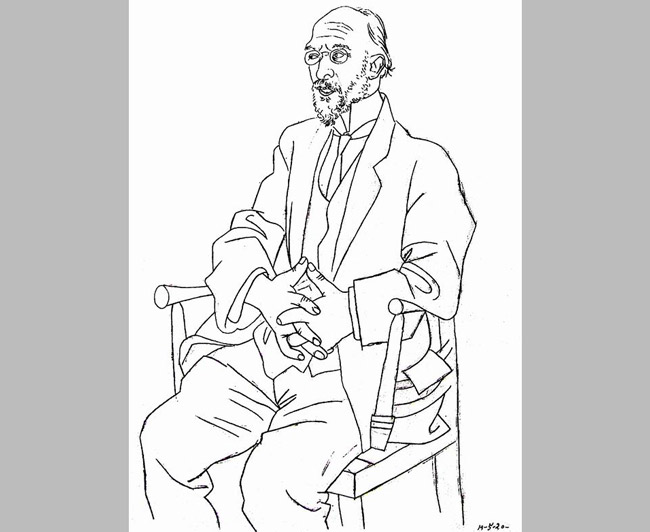

Undaunted, Picasso changes the subject. Tonight he wishes to talk about his portrait of Satie. He directs attention to the drawing of the sleeves, which he finds particularly elegant, and to the way in which he has caused the forms to tumble, not unlike Satie’s music.

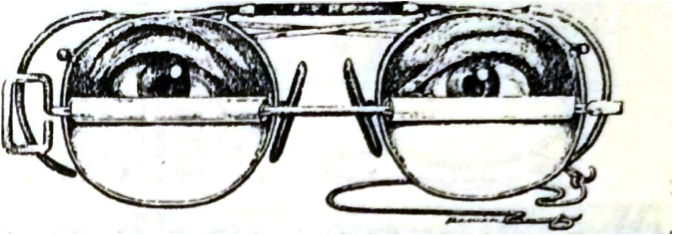

Drawing of Satie by Picasso.

Boccioni, stili smarting from the earlier remark about unfinished work, suggests that the sleeve on the left is more impressive than the sleeve on the right.

This topic excites Van Gogh, who expresses admiration for Picasso’s use of overlapping and spiraling, three-dimensional figures to bring life to that fine drawing. Vincent recalls with delight the first time he noted the device in the work of Delacroix. However, he confesses that he rarely used it to suggest the third dimension. Rather, it was the method which he used to cause objects in his work to twist, turn, and to serve as symbols for his own anguish. He expresses particular pleasure with his drawing of the man drinking tea, one in which the forms tick-tock, nod, and shift in a design metaphor of the old man’s conversational tempo and physical gestures.

Degas, who rarely condescends to participate in these exchanges, laments that laymen have misunderstood what truth in art is all about. Truth, he says, has to do with using the language of drawing knowledgeably, to alter and modify what one sees in a way, with respect to nature and to art, that represents one’s feelings and ideas. The final truth has everything to do with the arrangement of marks on a flat surface. With a nod to Michelangelo, he notes that all is design; distinctions of category are irrelevant.

At this point, Jacques Villon turns the conversation to Michelangelo’s use of geometrical systems in his plan for the Sistene Ceiling. Now, a fifteen year-old stowaway who has been hiding with us, can no longer contain his excitement and joins in the debate.

Without so much as an introduction, he tells Michelangelo of his excitement upon learning of the Master’s use of the square to bring unity to all of the prophets and sibyls in that vast design.

Flattered and amused, Michelangelo asks the boy whether he has noted the overlapping Root Two rectangles in those squares.

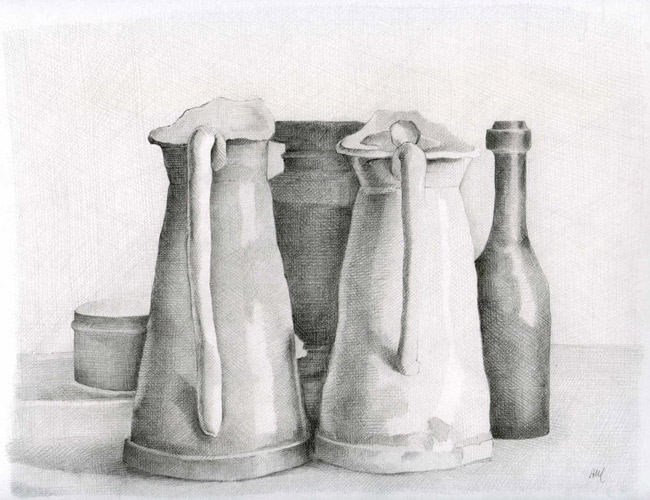

Delightedly, the young man begins his exposition of the subject which so fascinates him. He says that three years ago his art teacher, Mrs. Jones, had taught him the rabatment of the square, a technique that was easy to use, and that just last year Mr. Anderson had taught the Golden Section, using Michelangelo’s great composition as a model. Yes, he did know that there were overlapping Root Two rectangles in those squares, but what he admired most was the use of arabesquesto animate those figures.

“Mr. Anderson had assigned a project in which the Golden Section, the rabatment of the square, shifting two-dimensional rectangles and the arabesque were used to design a bottle,’’ he explained. “Then we used our studies to design and paint an abstraction. It was great fun, and I got an ‘A’ on the whole project!”

“When I took my work home,” he continued, “my parents framed the painting and hung it in the livingroom. Would you like to see some of the studies I did for the project? I just happen to have them with me.”